arXiv:2406.00735v1 [q-bio.BM] 02 Jun 2024

Jiahan LiChaoran ChengZuofan WuRuihan GuoShitong LuoZhizhou RenJian PengJianzhu Ma

Abstract

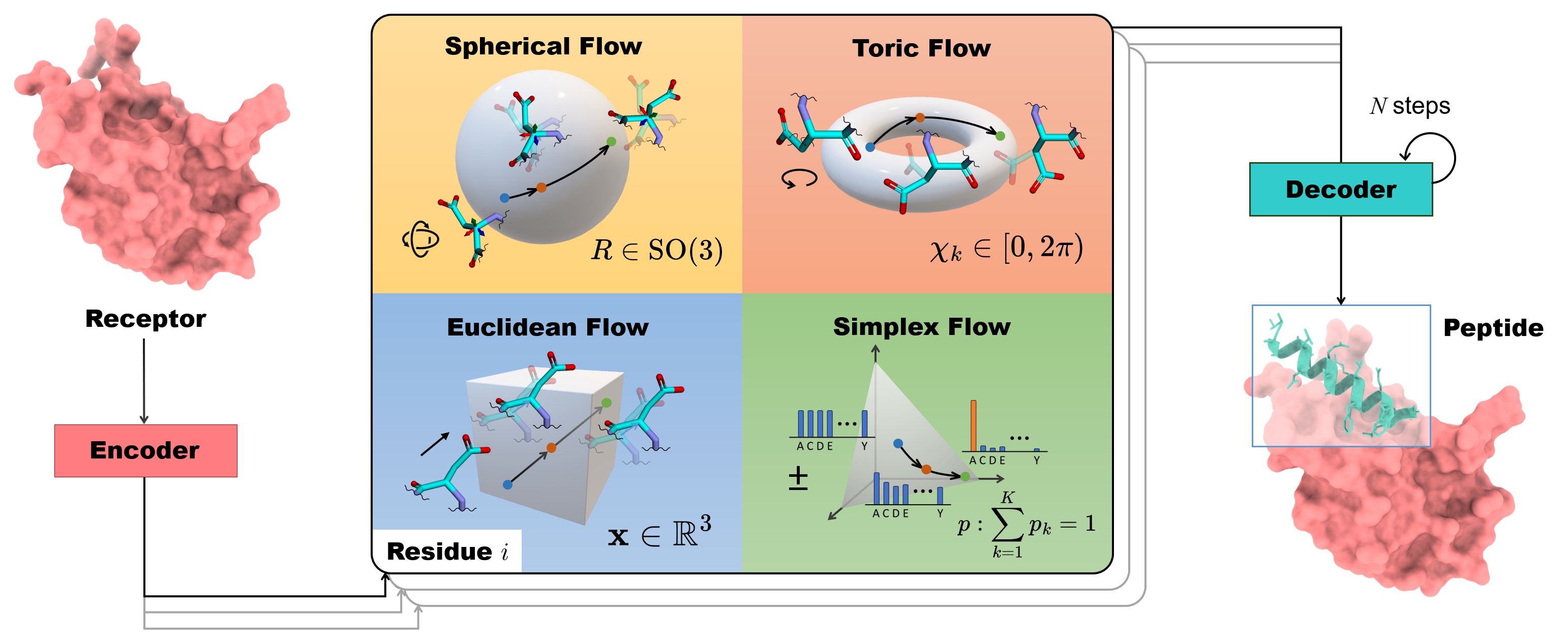

Peptides, short chains of amino acid residues, play a vital role in numerous biological processes by interacting with other target molecules, offering substantial potential in drug discovery. In this work, we present PepFlow, the first multi-modal deep generative model grounded in the flow-matching framework for the design of full-atom peptides that target specific protein receptors. Drawing inspiration from the crucial roles of residue backbone orientations and side-chain dynamics in protein-peptide interactions, we characterize the peptide structure using rigid backbone frames within the SE(3) manifold and side-chain angles on high-dimensional tori. Furthermore, we represent discrete residue types in the peptide sequence as categorical distributions on the probability simplex. By learning the joint distributions of each modality using derived flows and vector fields on corresponding manifolds, our method excels in the fine-grained design of full-atom peptides. Harnessing the multi-modal paradigm, our approach adeptly tackles various tasks such as fix-backbone sequence design and side-chain packing through partial sampling. Through meticulously crafted experiments, we demonstrate that PepFlow exhibits superior performance in comprehensive benchmarks, highlighting its significant potential in computational peptide design and analysis.

Machine Learning, ICML

1Introduction

Peptides, comprising approximately 3 to 20 amino-acid residues, are single-chain proteins (Bodanszky, 1988). By binding to other molecules, especially target proteins (receptors), peptides serve as integral players in diverse biological processes, such as cellular signaling, enzymatic catalysis, and immune responses (Petsalaki & Russell, 2008; Kaspar & Reichert, 2013). Therapeutic peptides that bind to diseases-associated proteins are gaining recognition as promising drug candidates due to their strong affinity, low toxicity, and easy delivery (Craik et al., 2013; Fosgerau & Hoffmann, 2015; Muttenthaler et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2022). Traditional discovery methods, such as mutagenesis and immunization-based library construction, face limitations due to the vast design space of peptides (Lam, 1997; Vlieghe et al., 2010; Fosgerau & Hoffmann, 2015). To break the experimental constraints, there is a growing demand for computational methods facilitating in silico peptide design and analysis (Bhardwaj et al., 2016; Cao et al., 2022; Xie et al., 2023; Manshour et al., 2023; Bryant & Elofsson, 2023; Bhat et al., 2023).

Recently, deep generative models, particularly diffusion probabilistic models (Sohl-Dickstein et al., 2015; Ho et al., 2020; Song & Ermon, 2019; Song et al., 2020b), have shown considerable promise in de novo protein design (Huang et al., 2016). These models mainly focus on generating protein backbones, represented as N rigid frames in the SE(3) manifold (Trippe et al., 2022; Anand & Achim, 2022; Luo et al., 2022; Wu et al., 2022; Ingraham et al., 2023; Yim et al., 2023b). The current state-of-the-art method, RFDiffusion (Watson et al., 2022) excels in designing a diverse array of functional proteins with an enhanced success rate validated through experiments (Roel-Touris et al., 2023).

Though achieving remarkable success in protein backbone design, current generative models still encounter challenges in generating peptide binders conditioned on a specific target protein (Bennett et al., 2023). Unlike unconditional generation, generating binding peptides necessitates explicit conditioning on binding pockets, as the bound-state structures of peptides in protein-peptide complexes partially depend on their targets (Duffaud et al., 1985; Dagliyan et al., 2011) and peptides contact accurate binding sites for biological functions. Furthermore, as shown in Figure 1, in protein-peptide interactions (Stanfield & Wilson, 1995; Jacobson et al., 2002), the focus should extend beyond the positions and orientations of the backbones to encompass the dynamics of side-chain angles, where residues interact with each other through non-covalent forces formed by side-chain groups. Consequently, peptide generation should consider full-atom structures rather than solely concentrating on modeling the four backbone heavy atoms. Also, since the structure of the functional peptide is mainly determined by its sequence (Whisstock & Lesk, 2003), it is essential to simultaneously consider sequence and structure during generation to enhance consistency between them.

To address the challenges mentioned above, we introduce PepFlow, a multi-modal deep generative model built upon the Conditional Flow Matching (CFM) framework (Lipman et al., 2022). CFM learns the continuous normalizing flow (Chen et al., 2018) by regressing the vector field that transforms prior distributions to target distributions. It has demonstrated competitive generation performance compared to the diffusion framework and is handy to adopt on non-Euclidean manifolds (Chen & Lipman, 2023). We further extend CFM to modalities related to full-atom proteins. In our framework, each residue in the peptide is represented as a rigid frame in SE(3) for backbone, a point on a hypertorus corresponding to side-chain angles, and an element on the probability simplex indicating the discrete type. We derive analytical flows for each modality and model the joint distribution of the full-atom peptide structure and sequence conditioned on the target protein. Subsequently, we can design full-atom peptides by simultaneously transforming from the prior distribution to the learned distribution on each modality. Our method extends its applicability to other tasks including fix-backbone sequence design and side-chain packing, which is achieved through partial sampling for desired modalities. Notably, there is no current comprehensive benchmark for evaluating generative models in peptide design, we further introduce a new dataset with in-depth metrics to quantify the qualities of generated peptides.

In summary, our key contributions include:

- • We introduce PepFlow, the first multi-modal generative model for designing full-atom protein structures and sequences

- • We pioneer the resolution of challenges in target-specific peptide design and establish comprehensive benchmarks, including newly cleaned dataset and novel in silico metrics to evaluate generated peptides.

- • Our method showcases superior performance and great scalability across a spectrum of peptide design and analysis tasks encompassing sequence-structure co-design, fix-backbone sequence design, and side-chain packing.

2Related Work

Diffusion-based and Flow-based Generative Models Trained on the denoising score matching objective (Vincent, 2011), diffusion models refine samples from prior Gaussian distributions into gradually meaningful outputs (Sohl-Dickstein et al., 2015; Ho et al., 2020; Song & Ermon, 2019; Song et al., 2020b). Diffusion models are applicable in diverse modalities, e.g. images (Ho et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2023a), texts (Austin et al., 2021; Hoogeboom et al., 2021) and molecules (Hoogeboom et al., 2022; Xu et al., 2022; Jing et al., 2022). However, they rely on stochastic estimation which leads to suboptimal probability paths and longer sample steps (Song et al., 2020a; Lu et al., 2022).

Another direction considers ODE-based continuous normalizing flows as an alternative to diffusion models (Chen et al., 2018). Conditional Flow Matching (CFM) (Lipman et al., 2022; Liu et al., 2022; Albergo & Vanden-Eijnden, 2022) directly learns the ODE that traces the probability path from the prior distribution to the target, regressing the pushing-forward vector field conditioned on individual data points. Additionally, Riemannian Flow Matching (Chen & Lipman, 2023) extends CFM to general manifolds without the requirement for expensive simulations (Ben-Hamu et al., 2022; De Bortoli et al., 2022; Huang et al., 2022). In our work, we use the flow matching framework to conditionally model full-atom structures and sequences of peptide binders. Though previous work existed in applying flow matching models in molecular generation (Song et al., 2023; Bose et al., 2023; Yim et al., 2023a, 2024), they mainly focused on specific modalities or unconditional generation.

De novo Protein Design with Generative Models Generative models have demonstrated promising performance in the design of protein-related applications including enzyme active sites (Yeh et al., 2023; Dauparas et al., 2023; Zhang et al., 2023c) and motif scaffolds (Wang et al., 2021; Trippe et al., 2022; Yim et al., 2024). These methods can be categorized into three main schemes: sequence design, structure design, and sequence-structure co-design. In sequence design, protein sequences are crafted using oracle-based directed evolution (Jain et al., 2022; Ren et al., 2022; Khan et al., 2022; Stanton et al., 2022), protein language models (Madani et al., 2020; Verkuil et al., 2022; Nijkamp et al., 2023), and discrete diffusion models (Alamdari et al., 2023; Frey et al., 2023; Gruver et al., 2024; Yi et al., 2024).Alternatively, sequences are sampled based on protein backbone structures, known as fix-backbone sequence design (Ingraham et al., 2019; Jing et al., 2020; Hsu et al., 2022; Li et al., 2022; Gao et al., 2022). Recognizing the important role of protein 3D structures, another approach involves directly generating protein backbone structures (Trippe et al., 2022; Anand & Achim, 2022; Luo et al., 2022; Wu et al., 2022; Ingraham et al., 2023). These backbones are then fed into fix-backbone design models to predict the corresponding sequences, e.g. ProteinMPNN (Dauparas et al., 2022). Sequence-structure co-design methods jointly sample sequence-structure pairs conditioned on provided information and find widespread usage in designing antibodies (Jin et al., 2021; Luo et al., 2022; Kong et al., 2022). Nevertheless, few methods focus on the interplay of side-chain interactions in the conditional generation of proteins or concurrently producing protein structures and sequences in full atomic detail (Martinkus et al., 2023; Kong et al., 2023; Krishna et al., 2023).

3Methods

3.1Preliminary

A protein is a biomolecule comprised of several amino acid residues, each characterized by its type, backbone frame, and side-chain angles (Fisher, 2001), as illustrated in Figure 1. The type of the i-th residue ai∈{1…20} is determined by its side-chain R group. The rigid frame is constructed by using the coordinates of four backbone heavy atoms N-Cα-C-O, with Cα located at the origin. Thus, a residue frame is parameterized by a position vector 𝐱i∈ℝ3 and a rotation matrix Ri∈SO(3) (Jumper et al., 2021). The side-chain conformation exhibits flexibility compared to the rigid backbone and can be represented as up to four torsion angles corresponding to rotatable bonds between side-chain atoms χi∈[0,2π)4. We further consider the rotatable backbone torsion angle ψi∈[0,2π) which governs the position of the O atom. Consequently, a protein with n residues can be sufficiently and succinctly parameterized as {(ai,Ri,𝐱i,χi)}i=1n, where χi[0]=ψi and χi∈[0,2π)5.

In this work, we focus on designing peptides based on their target proteins. Formally, given a n-residue peptide Cpep={(aj,Rj,𝐱j,χj)}j=1n and its m-residue target protein (receptor) Crec={(ai,Ri,𝐱i,χi)}i=1m, we aim to model the conditional joint distribution p(Cpep|Crec).

3.2Multi-modal Flow Matching

The conditional flow matching framework (Lipman et al., 2022) provides a simple yet powerful way to learn a probability flow ψ that pushes the source distribution p0 to the target distribution p1 of the data points 𝐱∈ℝd. The time-dependent flow ψt:[0,1]×ℝd→ℝd and the associated vector field ut:[0,1]×ℝd→ℝd can be defined via the Ordinary Differential Equation (ODE) ddt𝐱t=ut(𝐱t) where 𝐱t=ψt(𝐱𝟎). A time-dependent network vθ(𝐱t,t) can be used to directly regress the defined vector field, known as the Flow Matching objective (FM). However, the FM objective is intractable in practice, as we have no access to the closed-form vector field ut. Nonetheless, when conditioning the time-dependent vector field and probability flow on the specific sample 𝐱1∼p1(𝐱1) and the prior sample 𝐱0∼p0(𝐱0), we can model 𝐱t=ψt(𝐱0|𝐱1) and ut(𝐱t|𝐱0,𝐱1)=ddt𝐱t with the tractable Conditional Flow Matching (CFM) objective:

| ℒ(θ)=𝔼t,p1(𝐱1),p0(𝐱0)∥vθ(𝐱t,t)−ut(𝐱t|𝐱1,𝐱0)∥2 | (1) |

where t∼𝒰(0,1). It has been proved that the FM and CFM objectives have identical gradients with respect to the parameters θ, and we can integrate the learned vector field through time for sampling. Chen & Lipman (2023) further extended CFM to general geometries.

We employ the conditional flow matching framework to learn the conditional distribution of an n-residue peptide based on its m-residue target protein p(Cpep|Crec). We empirically decompose the joint probability into the product of probabilities of four basic elements that can describe the sequence and structure:

| p(Cpep|Crec) | ∝p({aj}j=1n|Crec)p({Rj}j=1n|Crec) | (2) | ||

| ⋅p({𝐱j}j=1n|Crec)p({χj}j=1n|Crec) |

We elaborate on the construction of different probability flows on the residue’s position p(xj|Crec), orientation p(Rj|Crec), torsion angles p(χj|Crec), and type p(aj|Crec) as follows. For simplicity, we initially focus on the single j-th residue in the peptide.

Euclidean CFM for Position

We first adopt Euclidean CFM for the position vector 𝐱j∈ℝ3. As a common practice, we choose the isotropic Gaussian 𝒩(0,I3) as the prior, and our target distribution is p(𝐱j|Crec). The conditional flow is defined as linear interpolation connecting sampled noise 𝐱0j∼𝒩(0,I3) and the data point 𝐱1j∼p(𝐱j|Crec). The linear interpolation favors a straight trajectory, and such a property contributes to the efficiency of training and sampling, as it is the shortest path between two points in Euclidean space (Liu et al., 2022). The conditional vector field utpos is derived by taking the time derivative of the linear flow ψtpos:

| utpos(𝐱tj|𝐱1j,𝐱0j) | =𝐱1j−𝐱0j=𝐱1j−𝐱tj1−t | (4) |

We use a time-dependent translation-invariant neural network vpos to predict the conditional vector field based on the current interpolant 𝐱t and the timestep t. The CFM objective of the j th residue is formulated as:

| ℒjpos=𝔼t,p(𝐱1j),p(𝐱0j)‖vpos(𝐱tj,t,Crec)−(𝐱1j−𝐱0j)‖22 | (5) |

During generation, we first sample from the prior 𝐱0j∼𝒩(0,I3) and solve the probability flow with the learned predictor vpos using the N-step forward Euler method to get the position of residue j with t={0,…,N−1N}:

| 𝐱t+1Nj=𝐱tj+1Nvpos(𝐱tj,t,Crec) | (6) |

Spherical CFM for Orientation

The orientation of the residue j can be represented as a rotation matrix Rj∈SO(3) concerning the global frame. The 3D rotation group SO(3) is a smooth Riemannian manifold and its tangent 𝔰𝔬(3) is a Lie group containing skew-symmetric matrices. An element in 𝔰𝔬(3) can also be interpreted as an infinitesimal rotation around a certain axis and characterized as a rotation vector in ℝ3 (Blanco-Claraco, 2021). We choose the uniform distribution over SO(3) as our prior distribution. Just as flow matching in Euclidean space uses the shortest distance between two points, we can envision establishing flows by following the corresponding geodesics in the context of SO(3) (Lee, 2018). Geodesics on SO(3) represent the paths of the minimum rotational distance between two orientations and provide a natural way to interpolate and evolve orientations in a manner that respects the underlying geometry of the rotation manifold (Bose et al., 2023; Yim et al., 2023a). The conditional flow ψori and vector field utori are established by the geodesic interpolation between R0j∼U(SO(3)) and R1j∈p(Rj|Crec) with the geodesic distance decreasing linearly by time:

| utori(Rtj|R0j,R1j) | =𝚕𝚘𝚐RtjR1j1−t | (8) |

where 𝚎𝚡𝚙 and 𝚕𝚘𝚐 are the exponential and logarithm maps on SO(3) that can be computed efficiently using Rodrigues’ formula (see Appendix A.1). A rotation-equivariant neural network vori is applied to predict the vector field, represented as rotation vectors. The CFM objective on SO(3) is formulated as:

| ℒorij=𝔼t,p(R1j),p(R0j)‖vori(Rtj,t,Crec)−𝚕𝚘𝚐RtjR1j1−t‖SO(3)2 | (9) |

where the vector field lies on the tangent space 𝔰𝔬(3) of SO(3) and the norm is induced by the canonical metric on SO(3). During inference, we initiate the process from R0j∼U(SO(3)) and proceed by taking small steps along the geodesic path in SO(3) over the timestep t:

| Rt+1Nj=𝚎𝚡𝚙Rtj(1Nvori(Rtj,t,Crec)) | (10) |

Toric CFM for Angles

An angle taking values in [0,2π) can be represented as a point on the unit circle 𝕊1, and the torsion vector χj consisting 5 angles lies on the 5-dimensional flat torus 𝕋d=(𝕊1)5 as the Cartesian product of 5 one-dimensional unit circles. The flat torus 𝕋5 can also be viewed as the quotient space ℝ5/(2πℤ)5 that inherits its Riemannian metric from Euclidean space. Therefore, the exponential and logarithm maps are similar to those in Euclidean space except for the equivalence relation about the periodicity of 2π. We choose the uniform distribution on [0,2π]5 as the prior distribution, and the conditional flow between sampled points χ0j∼U([0,2π]5) and χ1j∼p(χj|Crec) is constructed along the geodesic:

| utang(χtj|χ0j,χ1j) | =wrap(χ1j−χtj1−t) | (13) |

A neural network vang is applied to predict the vector field that lies on the tangent space of 𝕋5, leading to the CFM objective on torus as:

| ℒangj=𝔼t,p(χ1j),p(χ0j)‖wrap(vang(χtj,t,Crec)−χ1j−χ0j1−t)‖2 | (14) |

Instead of using the standard distance of the Euclidean space, we use the flat metric on 𝕋d for comparing the predicted and ground truth vector field, which enhances the network’s awareness of angular periodicity on the toric geometry. During inference, we take Euler steps from prior sample points χj∼U([0,2π]5) along the geodesic path in 𝕋5:

| χt+1Nj=(χtj+1Nvang(χtj,t,Crec))%2π | (15) |

Simplex CFM for Type

The above flow-matching methods apply to values in continuous spaces. The residue type aj∈{1…20}, however, admits a discrete categorical value. To map the discrete residue type aj to a continuous space, we adopt a soft one-hot encoding operation 𝚕𝚘𝚐𝚒𝚝(aj)=𝐬j∈ℝ20 with a constant value K>0, and the i-th value in 𝐬j is

| 𝐬j[i]={K,i=aj−K,otherwise | (16) |

𝐬j can be understood as the logits of the probabilities (Han et al., 2023), and 𝚜𝚘𝚏𝚝𝚖𝚊𝚡(𝐬j) becomes a normalized probability distribution with the j-th term close to 1 and other terms close to 0. This representation promotes the underlying categorical distribution with a probability mass centered on the correct residue type aj. In other word, 𝚜𝚘𝚏𝚝𝚖𝚊𝚡(𝐬j) is a point on the 20-category probability simplex Δ19. The d-categorical probability simplex Δd−1:={𝐱∈ℝd:0≤𝐱[i]≤1,∑i=1d𝐱[i]=1} is a smooth manifold in ℝd (Wang & Carreira-Perpinán, 2013; Richemond et al., 2022; Floto et al., 2023), where each point in Δd−1 represents a categorical distribution over the d classes. Though we can directly perform flow matching on Δd−1 (Li, 2018), we choose to construct conditional flow on the logit space in ℝd. We choose our prior distribution of logit as 𝒩(0,K2I) such that the prior distribution on simplex becomes the logistic-normal distribution by construct (Atchison & Shen, 1980). The conditional flow ψttype and vector field on the logit space is defined as:

| uttype(𝐬tj|𝐬1j,𝐬0j) | =𝐬1j−𝐬0j=𝐬1j−𝐬tj1−t | (18) |

The linear interpolations between 𝐬1j and 𝐬0j induce a geometric mean of the prior logit-normal distribution and target distribution p(aj|Crec). This induces a time-dependent interpolant between points on the probability simplex, capturing the evolving relationship between the prior and target distributions. Similarly, a neural network vtype is applied to predict the vector field on the logit space, and the CFM objective is:

| ℒjtype=𝔼t,p(𝐬1j),p(𝐬0j)‖vtype(𝐬tj,t,Crec)−(𝐬1j−𝐬0j)‖22 | (19) |

During inference, we perform Euler steps to solve the probability flow on the logit space, residue types can be sampled from the corresponding probability vector on the simplex:

| at+1/Nj | ∼𝚜𝚘𝚏𝚝𝚖𝚊𝚡(𝐬t+1Nj) | (21) |

To improve generation consistency between the logit and simplex space, we additionally map the predicted discrete residue back to the logit space during each iteration as 𝐬t+1/Nj=𝚕𝚘𝚐𝚒𝚝(at+1Nj).

Combining all modalities, we obtain the final multi-modal conditional flow matching objective for residue j as the weighted sum of different conditional flow matching objectives:

| ℒcfmj=𝔼t(λposℒjpos+λoriℒjori+λangℒjang+λtypeℒjtype) | (22) |

After discussing the multi-modal flow for modeling the factorized distribution of position, orientation, residue type, and side-chain torsion angles for a single residue j, we further extend our method for modeling the joint distribution p(Cpep|Crec) in the following subsection.

3.3PepFlow Architecture

Network Parametrization

As the joint distribution of the peptide is conditioned on its target protein receptor, we employ a geometric equivariant encoder to capture the context information of the target protein. Conversely, the above flow matching model can be viewed as a decoder for regressing the vector fields of the generated peptide, as depicted in Figure 2. In the model pipeline, the encoder Enc takes the sequence and structure of the target protein Crec, producing the hidden residue representations 𝐡 and the residue-pair embedding 𝐳. Subsequently, we sample a specific timestep t∼U(0,1) to construct the multi-modal flows where time-dependent vector fields are learned simultaneously for each modality of the peptide Cpep. The time-dependent decoder network Dec, mainly based on the Invariant Point Attention scheme (Jumper et al., 2021), takes the timestep t, the interpolant state of the peptide Ctpep={(𝐬tj,Rtj,𝐱tj,χtj)}j=1n, and the residue and pair embeddings as input. Rather than directly regressing the vector fields, the decoder first recovers the original peptide C¯1pep={(𝐬¯1j,R¯1j,𝐱¯1j,χ¯1j)}j=1n which allows for better training efficiency and the use of auxiliary loss. In this way, the CFM objectives for different modalities are reparametrized as the distance between the vector fields derived from ground truth elements and those derived from predicted elements (see Appendix A.2). The overall training objective is the sum of reparameterized CFM objectives, considering the expectation over each timestep and each residue in the peptide.

| ℒ=𝔼t[1n∑j(ℒcfmj+λaux(ℒbbj+ℒtorj))] | (23) |

Here we also use the backbone position loss ℒbb and the torsion angle loss ℒtor as auxiliary structure losses to improve the generation quality, incorporating information from different modalities (see Appendix A.5). The training process is outlined in Algorithm 1.Algorithm 1 Training Multi-Modal PepFlow

1:while not converged do

2: Sample protein-peptide pair Crec,Cpep

from dataset

3: Encode target 𝐡,𝐳=Enc(Crec)

4: Sample prior state C0pep={(a0j,R0j,x0j,χ0j)}j=1n

5: Sample t∼U(0,1)

6: Decode predicted peptide C¯pep=Dec(Ctpep,t,𝐡,𝐳)

7: Calculate the vector fields and the loss according to Eq.(23)

8: Update the parameters of Enc

and Dec

9:endwhile

Sampling Process

The sampling algorithm is outlined in Algorithm 2. During sampling, the target protein is encoded only once and is fed into each step of decoding. Initially, a prior state of the peptide is sampled. Subsequently, for each timestep of the sampling, the decoder predicts the recovered peptide state, and vector fields are calculated for each modality of the current state. The current state of the peptide is then updated using the Euler method following the derived vector fields, and the updated peptide is considered as the input of the decoder in the subsequent iteration. In the final step, we reconstruct the full-atom peptide using local coordinate transformations of the backbone and side-chain rigid groups (Jumper et al., 2021).

Noticeably, for a specific residue, the generation of a particular modality is not only dependent on the update of that modality but also influenced by the states of other modalities and other residues within the peptide. This interdependence highlights the intricate relationship between different modalities and residues, illustrating the complex nature of the joint distribution captured by our designed decoder network.Algorithm 2 Sampling with Multi-Modal PepFlow

1: Encode target 𝐡,𝐳=Enc(Crec)

2: Sample prior state C0pep={(a0j,R0j,x0j,χ0j)}j=1n

3:fort←1

to N

do

4: Decode predicted peptide C¯tNpep=Dec(Ct−1Npep,t,𝐡,𝐳)

5: Calculate vector fields and update the peptide CtNpep=EulerStep(C¯tNpep,Ct−1Npep,1N)

6:endfor

7:return C¯1pep

Furthermore, beyond the joint design of sequences and structures, we can construct partial states tailored for peptide design tasks that specifically emphasize the generation of a particular modality while keeping other modalities fixed. In the context of side-chain packing, we maintain the ground truth sequence and the backbone structure (i.e., types, positions, and orientations), and exclusively sample the torsion angles. Conversely, in fix-backbone sequence design, our focus lies in sampling sequences while holding constant the backbone positions and orientations.

4Experiment

Table 1:Evaluation of methods in the sequence-structure co-design task.

| Geometry | Energy | Design | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AAR %↑ | RMSD Å↓ | SSR %↑ | BSR %↑ | Stability %↑ | Affinity %↑ | Designability %↑ | Diversity ↑ | |

| RFdiffusion | 40.14 | 4.17 | 63.86 | 26.71 | 26.82 | 16.53 | 78.52 | 0.38 |

| ProteinGenerator | 45.82 | 4.35 | 29.15 | 24.62 | 23.48 | 13.47 | 71.82 | 0.54 |

| Diffusion | 47.04 | 3.28 | 74.89 | 49.83 | 15.34 | 17.13 | 48.54 | 0.57 |

| PepFlow w/Bb | 50.46 | 2.30 | 82.17 | 82.17 | 14.04 | 18.10 | 50.03 | 0.64 |

| PepFlow w/Bb+Seq | 53.25 | 2.21 | 85.22 | 85.19 | 19.20 | 19.39 | 56.04 | 0.50 |

| PepFlow w/Bb+Seq+Ang | 51.25 | 2.07 | 83.46 | 86.89 | 18.15 | 21.37 | 65.22 | 0.42 |

In this section, we conduct a comprehensive evaluation of PepFlow across three tasks: (1) Sequence-Structure Co-design, (2) Fix-Backbone Sequence Design, and (3) Side-Chain Packing. We introduce a new benchmark dataset derived from PepBDB (Wen et al., 2019) and Q-BioLip (Wei et al., 2024). After removing duplicate entries and applying empirical criteria (e.g. resolution <4Å, peptide length between 3−25), we cluster these complexes according to 40% peptide sequence identity using mmseqs2 (Steinegger & Söding, 2017). This results in 8,365 non-orphan complexes distributed across 292 clusters. To construct the test set, We randomly select 10 clusters containing 158 complexes, while the remaining complexes are used for training and validation.

We implement and compare the performance of three variants of our model. PepFlow w/Bb only samples backbones; PepFlow w/Bb+Seq is used for modeling backbones and sequences jointly; and PepFlow w/Bb+Seq+Ang finally model the full-atom distributions of peptides. Experimental details and additional results are provided in Appendix B.

4.1Sequence-Structure Co-design

This task requires the generation of both the sequence and bound-state structure of the peptide based on its target protein. Models take the full-atom structure of the target protein as input and generate bound-state peptides. We generate 64 peptides for each target protein for every evaluated model.

Baselines We use two state-of-the-art protein design models as baselines. RFDiffusion (Watson et al., 2022) generates protein backbones, and sequences are later predicted by ProteinMPNN (Dauparas et al., 2022). ProteinGenerator (Lisanza et al., 2023) improves RFDiffusion by jointly sampling backbones and corresponding sequences. These two methods do not consider side-chain conformations.

Metrics We assess the generated peptides from three perspectives. (1) Geometry. The generated peptides should exhibit sequences and structures similar to those of the native ones. The amino acid recovery rate (AAR) measures the sequence identity between the generated and the ground truth. The root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) aligns the complex by peptide structures and calculates the Cα RMSD. The secondary-structure similarity ratio (SSR) calculates the proportion of shared secondary structures. The binding site ratio (BSR) is the overlapping ratio between the binding site of the generated peptide and the native binding site on the target protein. (2) Energy. We aim to design high-affinity peptide binders that stabilize the protein-peptide complexes. Affinity is the percentage of the designed peptides with higher binding affinities (lower binding energies) than the native peptide, and Stability calculates the percentage of complex structures that are at more stable (lower total energy) states than the native ones. The energy terms are calculated by Rosetta (Alford et al., 2017). (3) Design. Designablity measures the consistency between generated sequences and structures by counting the fractions of sequences that can fold into similar structures as the corresponding generated structure. We utilize ESMFold (Lin et al., 2023) to refold sequences and use Cα RMSD <2Åas designable criteria. Diversity is the average of one minus the pair-wise TM-Score (Zhang & Skolnick, 2005) among the generated peptides, reflecting structural dissimilarities.

Results As indicated in Table 1, PepFlow is capable of generating peptides that closely resemble native ones with improved binding affinities. The distributions of generated backbone torsion angles also closely align with the native peptide distributions (see Figure 3). Since the generation of structure and sequence is decoupled, RFDiffusion exhibits the lowest recovery, whereas PepFlow achieves lower RMSD and higher AAR by incorporating the sequence modality. Moreover, the explicit modeling of side-chain conformations effectively captures the fine-grained structures in protein-peptide interactions, enhancing the ability of generated peptides to accurately bind to designated binding sites. Consequently, the proportion of peptides with higher affinity is also increased. We also observe that baselines outperformed our models in terms of Stability and Designability, probably because they are trained on the entire PDB structures and are biased toward structures with more stable motifs. Additionally, we note that modeling more modalities leads to a slightly lower diversity of refolded structures. Nevertheless, our results demonstrate that incorporating sequence and side-chain conformation, beyond modeling the backbone, significantly improved the model’s performance, underscoring the importance of full-atom modeling.

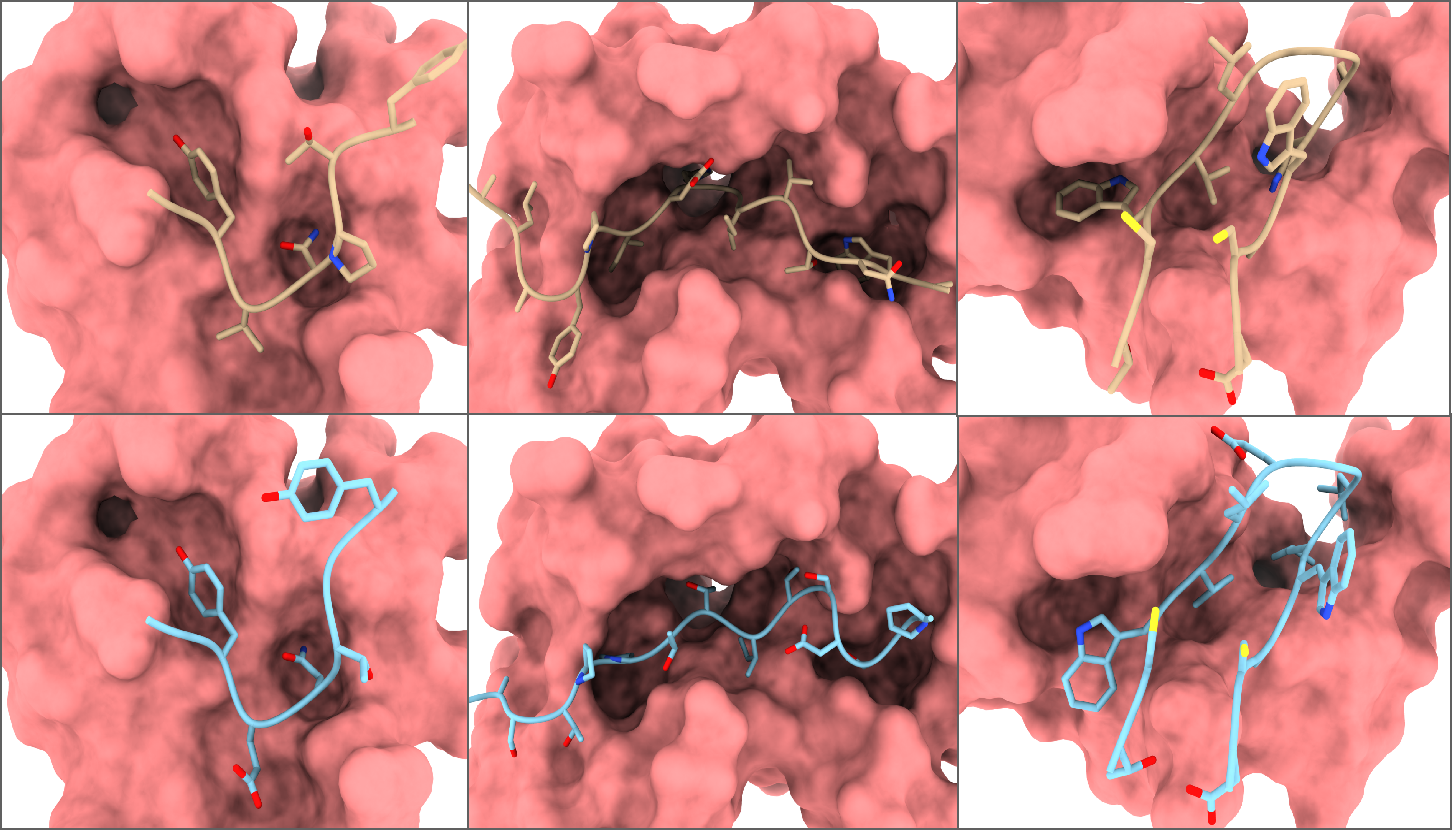

Visualizations We further present three examples of generated full-atom peptides generated by full-atom PepFlow in Figure 4. We observe that PepFlow consistently produces peptides with topologically resembling geometries, regardless of the native length. Remarkably, the generated peptides exhibit similar side-chain compositions and conformations, facilitating effective interaction with the target protein at the correct binding site.

4.2Fix-backbone Sequence Design

This task involves designing peptide sequences based on the structure of the complex without side-chains. We generate 64 sequences for each peptide using each model. For our models, we apply the partial sampling scheme to recover the sequence.Table 2:Evaluations of methods in the fix-backbone sequence design task.

| AAR %↑ | Worst %↑ | Likeness ↓ | Diversity ↑ | Designbility %↑ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ProteinMPNN | 53.28 | 45.99 | -8.42 | 15.33 | 60.55 |

| ESM-IF | 43.51 | 36.18 | -8.39 | 13.76 | 53.76 |

| PepFlow w/Bb+Seq | 56.40 | 46.59 | -8.26 | 23.38 | 59.72 |

| PepFlow w/Bb+Seq+Ang | 54.32 | 44.48 | -8.58 | 20.65 | 65.48 |

Baselines We use two inverse folding models which can design peptide sequences conditioned on the rest of the complex as our baselines: Protein-MPNN (Dauparas et al., 2022), a GNN-base model, and ESM-IF (Hsu et al., 2022), based on GVP-Transformer (Jing et al., 2020).

Metrics In addition to AAR used in co-design task, we calculate Worst as the lowest recovery rate. Likeness is the negative log-likelihood score of the sequence from ProtGPT2 (Ferruz et al., 2022), indicating how closely the generated sequence aligns with the native protein distribution. Diversity represents the average pairwise Hamming Distance between generated sequences.

Results As presented in Table 2, our models achieve higher recovery rates and better diversities, showcasing the effectiveness of our proposed simplex flow matching. We also observe a slight decrease in the recovery rate with the inclusion of angle modeling. This might be attributed to the fact that some amino acids share similar side-chain compositions and physicochemical properties (e.g. Ser and Thr, Arg and Lys), leading the model to generate a physicochemically feasible but different residue. Generating both the sequences and side-chain angles leads to higher likeness and lower diversity.

4.3Side-chain Packing

This task predicts the side-chain angles of the peptide. We generate 64 side-chain conformations for each peptide by each model and apply the partial sampling scheme of our model to recover side-chain angles.Table 3:Evaluation of methods in the side-chain packing task.

| MSE ↓∘ | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| χ1 | χ2 | χ3 | χ4 | Correct %↑ | |

| Rosseta | 38.31 | 43.23 | 53.61 | 71.67 | 57.03 |

| SCWRL4 | 30.06 | 40.40 | 49.71 | 53.79 | 60.54 |

| DLPacker | 22.44 | 35.65 | 58.53 | 61.70 | 60.91 |

| AttnPacker | 19.04 | 28.49 | 40.16 | 60.04 | 61.46 |

| DiffPack | 17.92 | 26.08 | 36.20 | 67.82 | 62.58 |

| PepFlow w/Bb+Seq+Ang | 17.38 | 24.71 | 33.63 | 58.49 | 62.79 |

Baselines Two energy-based methods: RossettaPacker (Leman et al., 2020), SCWRL4 (Krivov et al., 2009), and learning-based models: DLPacker (Misiura et al., 2022), AttnPacker (McPartlon & Xu, 2022), DiffPack (Zhang et al., 2023b).

Metrics We use the Mean Absolute Error (MAE) of predicted four torsion angles. Due to the flexibility of side-chains, We also include the proportion of the Correct predictions that deviate within 20∘ around the ground truth.

Results As shown in Table 3, our partially sampling PepFlow outperforms all other baselines across all four side-chain angles. Notably, χ1 and χ2 angles are easier to predict than χ3 and χ4. Our method also achieves the best correct rates, as our proposed toric flow can precisely capture the reasonable distribution of the side-chain angles and the plausible side-chain dynamics during the interaction between peptides and target proteins.

5Conclusion

In this study, we introduced PepFlow, a novel flow-based generative model tailored for target-specific full-atom peptide design. PepFlow characterizes each modality of peptide residues into the corresponding manifold and constructs analytical flows and vector fields for each modality. Through multi-modal flow matching objectives, PepFlow excels in generating full-atom peptides, capturing the intrinsic geometric characteristics across different modalities. In our newly designed comprehensive benchmarks, PepFlow has demonstrated promising performance by modeling full-atom joint distributions and exhibits potential applications in protein design beyond peptides, such as antibody and enzyme design. Nevertheless, PepFlow faces limitations in diversity during generation, stemming from the deterministic nature of ODE-based flow. Furthermore, its current incapability for property-guided generation, a common requirement in protein optimization, represents an area for improvement. Despite these considerations, PepFlow stands out as a potent and versatile tool for computational peptide design and analysis.

Impact Statement

PepFlow can contribute to the advancement of computational biology, particularly in the field of protein design, offering a valuable tool for designing therapeutic peptides with potential benefits for human health. While our primary focus is on positive applications, such as drug development and disease treatment, we recognize the importance of considering potential risks associated with any powerful technology. There is a possibility that our algorithm could be misused for designing harmful substances, posing ethical concerns. However, we emphasize the responsible and ethical use of our tool, urging the scientific community and practitioners to employ it judiciously for constructive purposes. Our commitment to ethical practices aims to ensure the positive impact of PepFlow on society.